Home · Email · List of Projects · Project Sites and Links · Articles · Robert Davis Biography

Design of Crossover Corridors

Actors and other staff need to cross over -- from one side of the stage to the other -- unseen by the audience. The audience can see the whole stage. Therefore an offstage crossover passageway is required. Ideally the crossover is an extension on the back of the stage simply for the purpose of running from one side of the stage to the other unseen.

Non-theater folks misunderstand this function to such a degree that often the crossover is planned poorly or omitted. Theater folks know in their bones what a crossover does and know what is required to make one work. The crossover is a fundamental part of stage planning.

Many technical assessments of stages have been done. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, for example, commissioned a statewide technical assessment of all existing theaters. These technical summaries give all the pertinent facts about a stage that a production's technical director would need when planning a visit to that theater. The crossover counts heavily in the assessment. For example, when a two or three page technical survey is done of a theater, the existence or absence of an adequate crossover is often the fourth or fifth piece of information reported. Name? Location? Width? Depth? Crossover? This should give some idea of the rank that a crossover holds in the relative importance of stage facilities. The crossover ranks very high in importance.

When an actor or technician tells friends about a theater they worked in recently, the lack of a crossover is often used to ridicule the theater. "I just played that barn. We sold out, but the crossover was in a dirt alley and it rained every day, so in the second act everybody was covered in mud from the waist down." "I did summer stock, and the crossover was an open wood balcony stuck on the back of the stage house about 30 feet in the air." The cast and crew know what a crossover does for them and they know that the lack or inadequacy of a crossover makes them miserable.

If there can't be a crossover at stage level, then the technical staff is interested in just how one does get across the stage without being seen. A crossover below the stage through the trap room or an exterior crossover in the alley behind are both possible substitutes for a crossover at stage level. Both are vastly inferior to having an interior crossover at stage level.

Visitors who are not familiar with the facility are often required to use the crossover in a hurry, in the dark, and in costume. It might be their first and only day in that particular theater, but they still have to perform perfectly. We know of career-ending injuries that resulted from bad spills on crossover stairs. We urgently recommend that crossovers be located at stage level, without steps, that they be enclosed, dry, non-skid, and safe.

The crossover has two basic variants, the good one and the bad one. The good crossover is an extension of the stage, same flooring, open to the stage, no doors, just not as high.

How high? Well, at least a legal height of 8 feet clear or so. But costumes and props such as spears often are much higher than 8', so the recommended minimum for a crossover and the openings that connect it to the stage is about 12', and anything higher is extremely helpful and useful.

The good crossover is seamlessly connected to the stage, except for its height, and has the same worklights, running lights, flooring, walls, and in fact it is just more stage, but not quite as high. The good crossover has lots of uses aside from running around behind the stage. The good crossover is well-connected and open to the stage, so it can be used for backings, for temporary storage, for projection equipment, for escape stairs, for extra wagon travel and, when the production really needs it, the good crossover can be used as more stage space, which is really what it is. The good crossover can be obstructed by scenery and can be made totally dark whenever the production needs it to be obstructed or dark. The good crossover can be used in complete silence and total darkness.

The bad crossover is also doubling as a legal means of egress corridor. Corridors are legally defined in building codes; they are fire rated, enclosed with latched doors, can't be open to the stage, and they are lighted AT ALL TIMES with a minimum light level. When things really get bad the corridor is shared with other tenants of the building and therefore is kept locked.

Using the bad crossover, the actor opens the fire-rated latched door with a clack, lets it close with a clack, while the door is open the noise from people talking in the corridor leaks into the stage, while the door is open the light from the corridor streams across the stage, the actor -- possibly semi-nude and "in-character" -- rubs shoulders with "civilians" in the corridor which is embarrassing for everybody and breaks the actor's concentration completely, the actor loses their dark-adaptation in the bright corridor so they are semi-blind when they re-enter the darkened stage, wearing costume slippers the actor slips on the waxed tile floor, the actor finds they can't open the door on the other side of the stage because it accidentally got locked and ACTORS DON'T CARRY KEYS, the actor finally opens the door letting noise and light into the stage, and lets the door close behind them with a loud clack.

No theater person would ever design a crossover like that, but in the schematic design phase of planning a theater it's awfully hard to convince a design team to show what looks like two parallel corridors on the plan, one crossover attached to the stage and one legal means of egress corridor right next to it.

The really bad crossover has windows. The pretty bad crossover is also the dressing room corridor, which is a little more controlled and private than a public corridor, but it is still fire-rated, still must remain lighted at all times, still has latching doors, still is noisy, and still is not as good as a real crossover that is open to the stage.

Site and adjacency issues often jeopardize the crossover. When planning a large theater on a shallow lot, it's extremely hard to justify taking 5 or 6 feet of precious depth for the minimum crossover. Sometimes the architect objects to the exterior appearance of an 80' high fly tower that comes down cleanly and then bumps out 6 feet at the bottom for the crossover. Always the "value engineering" phase questions the "value" of the crossover. Just what is its value in dollars? A crossover could represent $100,000 worth of square feet in the building. Often the program omits the crossover so it becomes a struggle to add the square footage and dollars for the crossover later. The crossover is surprisingly big. While it is only 6 to 10 feet wide, it needs to run the full width of the stage and can be 80 feet long. It's hard to add 500 to 800 net square feet to a project if it was omitted in the program. Always include the crossover as net assignable space in the program. The required space is not going to be found in the net-to-gross ratio; the crossover is just too big for that.

The crossover is a very useful tool in helping to solve planning problems. The stage is extremely crowded. All the stage walls are over-subscribed with electrical stuff, doors, and stage equipment. The crossover provides wonderful unobstructed walls that are out of harms way and that are located an ideal distance away from stage operations. The crossover is an excellent place to locate egress doors, electrical equipment, mop sinks, standpipes, and other necessities.

Crossover behind stage with fire-rated doors at Trenton PAC.

Crossover open to stage at Williams College.

Crossover doubles as dressing room corridor at Indiana University.

Crossover doubles as scene bay at Wolf Trap.

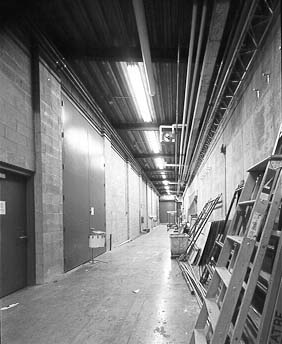

Crossover at Plymouth College.

This crossover at Plymouth College is also a legal means of egress, so the crossover is separated from the stage by fire rated doors. The corridor has white and blue worklights. There are two "elephant doors" from the crossover to the stage, one on each side of the stage. A personnel door flanks each "elephant door". These flanking personnel doors allow personnel to come and go freely when the big doors are closed. The loading dock is at one end of the crossover and the scene shop is at the other end. This crossover is dug deeply into a hillside.

Home · Articles