Home · Email · List of Projects · Project Sites and Links · Articles · Robert Davis Biography

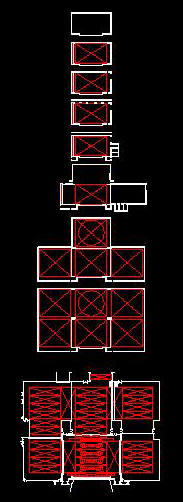

Proscenium Stages

Robert Davis Inc.

The basic proscenium stage is a rectangular box. Most stagecraft textbooks show this rectangular form. The rectangular form looks simple, but actually is tricky to plan because there is so little space in which to coordinate all the technical requirements. The rectangular stage plan can be improved with simple variations.

Rigging

Rigging occupies one whole side wall of the stage with no gaps or interruptions. With one whole wall covered by stage rigging the doors, electrical equipment, and everything else that needs to be on the rigging side of the stage must be located on the front and back walls. As a result the front and back walls become very cluttered. In our practice we use the term "oversubscribed" for these front and back walls that have so much stuff on them. We assume here that single purchase counterweight rigging is used. There are other types of rigging that we won't discuss here.Two thirds of all stages in the US have the rigging on the Stage Right side, one third have the rigging on the Stage Left side. In our projects we recommend that the rigging should be located on the Stage Right side unless there is some compelling reason to put it on Stage Left.

Doors

A normal stage has 5 doors -- two pass doors, two egress doors, and one loading door. A stage can have many other doors as well."Pass doors" are doors through the proscenium wall that allow staff to "pass" from the stage to the house privately, easily and quickly during working hours. "Pass doors" have no other function. The staff members who use these doors are not normally actors or stagehands. The pass doors are used by directors, designers, producers and other "management" staff. Usually one pass door is located on each side of the proscenium wall. It is best that the pass doors have no other use; pass doors are not a legal means of egress for the house or the stage. In architectural language these are "communicating doors" only. Pass doors are always used in a hurry so they should not be labyrinths. The pass doors must be accessible or an equivalent parallel accessible path of travel must be provided.

Building codes usually require a legal means of egress (exit door) on each side of the stage. These legal means of egress are not the pass doors.

The stage needs one loading door as a minimum, and sometimes more. Loading doors may lead directly to the exterior, but preferably lead to a loading bay. Loading doors that lead directly to the exterior let in noise and weather even when they're closed. Loading door size depends entirely on the needs of the users, and is too variable to discuss here.

Large scenery doors are slow and difficult to open and there are times during rehearsal and performance when they shouldn't be opened. Therefore each loading door needs to be flanked by a personnel door. We don't know of a legal way to place a personnel door in a loading door so they must be two separate doors.

Doors should not be placed on the back wall of the stage between the batten ends for obvious reasons: If placed behind the battens the doors would be covered by scenery. The back wall is very tempting as a location for the loading door, but should be avoided. It is likely that a lot of scenery and lighting is located immediately against of the back wall. This would include the ground row in a production with a cyclorama or might be a two-story unit or backings for a box set. In any case, it is likely that the cost of removing the upstage scenery and lighting to gain access to an upstage loading door would be very high. Locating the loading door up center is a mistake.

At this point one begins to appreciate that most of the stage is not available for doors. The proscenium opening is not available, a side stage is not available because it's filled with scenery, the rigging wall is not available, the proscenium walls left and right of the opening are not available, and the upstage wall within the batten length is not available. This leaves the end of the rear wall opposite the rigging and the side wall opposite the rigging as the only locations available for doors. The structural engineer usually needs the corners of the stage house to be filled with structure, so there are limits on how far doors, especially a big loading door, can be pushed toward the corners.

The Crossover

The crossover allows staff to cross over behind the stage out of view of

the audience. The ideal crossover is simply 5' to 10' more stage space across

the back of the stage, except it doesn't have to be as high as the gridiron. Ideally the

crossover is not used as a legal means of egress, as access to any other spaces,

or for any other purpose. Actors using the crossover must remain dark adapted, so the crossover must be very dark, so a legal means of egress that needs to be lit brightly at all times is not usful as a crossover and vice versa.

Niches and Closets

Renovated older theaters have niches in the proscenium wall, just offstage of the stage manager, where the switchboard used to be located. When the Grand Master resistance or autotransformer switchboard was removed a vacant niche remained. It turns out that the niche is really useful. Many new theaters, the Metropolitan Opera House and the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center for example, have a niche or niches in the same place because of the convenience and utility of having niches there even though they are new theaters where the niches are intentional, not accidental. Many of the theaters we renovated, the Victoria Theatre in Dayton for example, reused the old switchboard niche for new equipment and personnel.Almost any "department" should have a niche. A "department" is one of the classic divisions of stagecraft, such as stage management, rigging, props, carpentry, electrics, special effects or sound. A carpenter's niche would have readily accessible tools, stepladders, and spare parts. The property department is not only responsible for props, they are responsible for all cleaning and for all food used onstage. A prop niche would include locked storage, a mop sink, and space for cleaning equipment. An electric department niche would include cables, lamps, color frames, repair tools, and perhaps the lighting control computer and a few electricians. A sound niche would include locked microphone storage, cables, microphone stands, patch bays, and perhaps the onstage sound mix location. Such niches provide a way for these services to be immediately available to the stage without being in the way.

Company switches -- the electrical disconnects that feed big portable electrical equipment such as sound, lights, welders, motors, projections, smoke machines and special effects -- are physically very big themselves. Company switches usually are not good neighbors, that is they want to be removed a little from other stage occupants. Company switches should remain lighted at all times through the performance. Company switches usually are accompanied by huge piles of heavy feeder cables. The company switches can't be elsewhere, they must be on the stage. Some building codes require that company switches must be on the same level of the stage as the devices they serve. For all these reasons it is highly desirable to create a niche for the company switches. Otherwise they will be in the way.

Orchestra Shell Storage

Ideally there is no orchestra shell to store. If there is a shell, and if pieces of the shell need to be stored on the stage, then an orchestra shell storage niche is required. In early planning an area of 300 to 500 square feet typically is held as an allowance for shell storage until a real shell design confirms the actual size of the required shell storage area. It should be obvious that this shell storage space must be higher than the shell, must not be obstructed, and must be connected to the stage with a doorway or passageway that is higher than the shell. In Amarillo Texas we planned a shell that travels whole into a large shell storage garage and can set or strike in 4 minutes. The technique of storing the shell whole is so helpful to scheduling the facility it is being incorporated into several other projects.Piano Storage

Building owners have individual preferences about musical instrument storage, and should get exactly the type of piano storage they feel they need. I recommend that security is paramount, and that at a minimum, the piano storage area should be secure. I also recommend that the space called "piano storage" will actually need to accommodate two pianos, a harpsichord, a rented celesta, a marimba and maybe a clavichord, too.More controversial topics include how close the storage needs to be located to the stage and whether or not it needs to have independent climate control. Proximity to the stage depends on competing demands for space. The piano storage space should be "as close as possible" to the stage, as interpreted appropriately for each project.

Ideally the piano storage space is climate conditioned. The stage may receive no air conditioning, heating, or humidity control for long periods of time, sometimes weeks or months. Musical instruments do not take that kind of treatment very well. An instrument could bust a sounding board, become untunable or worse if not kept in stable climate conditions. The need for climate control in the piano storage area depends completely on the type of institution that owns and manages the building, on the value of the instruments to be stored, and on the type of climate control provided for the stage. In a conservatory where the whole stage is conditioned for musical instruments 365 days a year, the need for additional treatment for the storage areas is small. But in a "road house", where the stage will be completely un-conditioned for extended periods and may be rented to hoodlums, the need for independent climate control of a secure instrument storage area is clear. Some facilities have two separate rooms, one for pianos and one for other instruments.

Organ Storage

Some organs are permanent, some are portable. Uihlein Hall in Milwaukee has a permanent organ on an elevator designed by George Izenour so it can sink into the stage floor and be covered with a stage floor trap that slides in from the sides. This type of trap is called a "sloat", a word that derives from an old German word for "slot". Some organs have "tracker" movements that require the keyboard and the pipes to be permanently connected with steel wires. Some pipe organs have vacuum driven pipes that must be permanent, but the organ console operates those pipes over a computer data link with one tiny data cable so the keyboard unit is highly portable and there can be multiple keyboards.The rule with accommodating an organ is to assume nothing, to find out the requirements of the particular organ that will be purchased, and to build the organ spaces exactly to suit the needs of that organ. The accommodations required for organs are highly inflexible. Unfortunately often the owner does not have an organ decision available when the building is being planned, and then the planning of proper accommodations for the organ is impossible.

Stairs and Ladders

Stairs are required to get access to upper levels of the stage house. We try to have no stairs that extend down to stage level, at least not on the stage. Stage level stairs on the stage are in the way. It is impossible to provide security for open stairs that come to stage level. We prefer to have a second-floor door into the stage house from adjacent second-floor space backstage that continues upward into the stage house upper levels as a stair. This eliminates the obstruction of having stage-level stairs on the stage and automatically provides security. There are some wonderful exceptions, where security is not a concern and the stairs are immediately offstage so they are convenient and not in the way, as was done successfully at Indiana University.We avoid ladders. Ship's ladders are no longer legal. "Alternating tread" stairs have a small devoted following but most people find them impossible and infuriating to use, so we avoid them.

We avoid circular stairs. Gene Kelly movies show circular stairs backstage so many people assume circular stairs are desirable. Circular stairs look good in movies, but are tortuous and impossibly inconvenient. It is hard to carry anything up or down a circular stair. A 70' climb in a circular stair will make you dizzy. And lastly, with a few exceptions, circular stairs are not legal as part of a means of egress, and so circular stairs cannot be used as the only means of egress from the upper levels of the stage.

The Arbor Pit

The arbor pit is a fundamental part of the rigging system, and is built to save money. When running any rigging set up and down, the arbor, not the pipe batten, hits its up and down limits of travel first. The arbor can be 9' long or longer. This loses roughly 9' of travel. Therefore the batten high trim is limited by the arbor length far below the grid. The pipe can't travel higher because the arbor has already hit the floor. This wastes the expense of building a high grid and high stage house. It is possible to regain the use of the otherwise wasted space between the high trim and the grid in several ways. We find the best way is to use an arbor pit. This pit gets the stage floor out of the way under the arbors and so extends the arbor travel downward below the stage level so the high trim can be extended up to the grid.This all sounds like hocus pocus until one takes the time to lay out the rigging both ways and compare the differences. An arbor pit has the same effect on the high trim as raising the stage house roof, and it's a lot cheaper. Arbor pits are not recent inventions, but still many people haven't heard of them, possibly because arbor pits are tucked out of the way and sort of invisible. Even though they are not often noticed arbor pits are mainstream stage technology today. Most new theaters have single purchase rigging and have an arbor pit.

Side Stages and Rear Stages

In opera and in classic European stage planning side and rear stages are intended to provide spaces exactly the same size as the stage into which whole sets can be rolled on full-stage wagons. These designs are characterized by how many full stage-size units are provided. These stages are each the full width, depth, and height of the main stage, with the exception that only the main stage has a fly tower and the other stages do not.Side and rear stages have uses outside opera as well. When the Roundabout theater company was in their 23rd street location they had a full rear stage. On their rear stage they built and rehearsed their next production while the current production played downstage. On the changeover day they demolished the current production and dragged the complete next production downstage losing minimal dark days between productions, then started the cycle over. This was very efficient.

The previous examples are conceptually simple, with auxiliary stages being used for whole stage sets. The more frequent, more important, and less well known uses are much more subtle and unpredictable. Every production at some time needs to "lose" something big. Maybe it's a life-size aluminum elephant (Pennsylvania Ballet), or the first act set, or maybe it's the chorus or the road boxes that need to go away. A side stage or rear stage is the place to lose stuff. Some productions need extreme depth beyond what a normal stage can provide. This depth may be for scenic projections or for "reveals" or for some extreme perspective effect. A rear stage provides the depth to do these things without the expense of building the fly tower all the way back to the uptage wall of the rear stage.

Many productions need sudden appearances onstage, known in the entertainment industry as "reveals", of very large things. In The Magic Flute a mountain must appear. Side and rear stages provide the means to surprise the audience with the appearance of something really big. This is the "How did they get that in here?" effect. It also saves money when the scenery can be stored whole rather than being disassembled to fit an inadequate storage space and then reassembled again later the same day. Recent developments include sealing off one of the side stages acoustically and providing it with an audience so it can be used as a rehearsal stage and/or as a small public venue without affecting the operation of the main stage (Copenhagen and Reykjavik). The old style of designing side stages, we guess because of the small size and high cost of available sites in urban settings, was to provide side stages and aisles to link them that are only as wide as the "net" scenery, about the same width as the proscenium opening. A recent trend instead is to provide sufficient width in the side stages and aisles between them to accommodate the masking and backings as well. With this newer, wider, style the scenery can arrive on stage with backings, side lighting, special effects on each side, all intact and operating. Yet another recent trend is to provide short travel lifts that allow the wagons to travel depressed. Previously wagons could only travel after they had been lifted to stage level, no longer flush, and then they were re-sunk flush after arriving. This is not quick or pretty to watch from the audience's point of view. Newer opera houses can sink the aisles as well as the stages to allow wagons to travel while sunk flush with the floor.

The Offstage Room

When a show comes off the trucks everything arrives packed in road boxes. The stage is super busy, oversubscribed. Where do the boxes go? A huge offstage room should be provided adjacent to or behind every stage. For lack of a better name we call this room, "The Huge Offstage Room". The object is to provide a big room with no fixed purpose so the production can use it for whatever it needs and the function can change from hour to hour. A more specific title would undermine the flexibility that makes this room is so useful. The huge offstage room is used for: rehearsal; catering dinner to the crew; storing road boxes; warming up the chorus; storing scenery and props between acts; temporary chorus dressing room; quick change rooms; touring symphony dressing rooms where each musician brings their own road box; overflow green room; or as a temporary scene shop for repairs to scenery damaged in transit. Real theaters have these rooms. From days touring various productions around the country I remember these rooms making the difference between an easy load-in/out and a tough load-in/out. The best huge offstage rooms that we know are in the Orange County Performing Arts Center in Costa Mesa, California and in the Filene Center II at Wolf Trap in Vienna, Virginia.Batten Length

There are two styles in common practice for the length by which the rigging battens extend past the proscenium opening. Short battens yield one type of flexibility while long battens yield another.In theaters where one production will play for years and the highest priority is flexibility not speed, the battens should be short, perhaps extending only 4' or less offstage of the opening. The advantage of short battens is that they can be brought in to the floor INSIDE fixed scenery and equipment such as tabs, booms, light ladders, and side scenery walls without striking the obstructions. The disadvantage is that these short battens often must be supplemented or extended to support legs and longer scenery. In a sit-down production, such as on Broadway, spotting extra lines and pipes for legs and long scenery is customary, and the design flexibility this method yields is needed and expected.

In theaters where different productions will come and go every day the highest priority is lowering the cost of moving the scenery in and out, so the kind of flexibility required is the ability to accommodate many different types of scenery quickly. In these in-and-out quick theaters the battens should be long, extending as much as 12' or more past the opening. The advantage of long battens is that the crew seldom needs to stop what they're doing to extend a batten to accept long scenery or long masking pieces. The disadvantage is that more often battens can't be brought to the floor because their ends are blocked by offstage equipment such as lighting towers, offstage scenery, speakers, tabs, and backings.

Most theaters do a combination of both sit-down long term bookings and short bookings, so we normally recommend that battens extend roughly 8' past the opening. This medium length is optimum where one doesn't know what type of scenery will come in the door next. These battens can be extended when needed, supplemented with offstage battens when needed, cut off with difficulty when needed, and are not so long that they get in the way all the time. The european standard is to use much shorter battens. Some opera companies rig the ends of their light pipes on separate arbors so they can choose on a moment's notice whether or not to bring the batten ends in to the floor without cutting or re-rigging them. Modern theaters in Europe have light pipes composed of several short sections so the sections can be set at any height needed, not all the same, and so any obstruction can be avoided simply by not lowering the obstructed sections.

Proscenium Width and Height

Most rules of thumb for height and width are useless or harmful. I won't promote or dignify them by repeating them here.The proscenium opening should be as high as possible, without limit. Of course the fire curtain should still work, if there is one, but we find no benefit in lowering the architectural opening, there is only benefit in raising it.

The grid should be as high as possible, without limit. Most commercial stages in the US have gridirons that are higher than 72' above the finished stage floor. The building roof is normally about 12' higher than the grid.

The proscenium width should fit exactly the needs of the performing company. A proscenium opening that is too wide causes as much harm as an opening that is too narrow.

The stage house should be as wide as possible, without limit. It is never desirable to make the stage house narrower.

The stage should be as deep as possible, without limit. It is never desirable to make the stage shallower.

One thought experiment, actually built in some theaters, is that there doesn't need be a proscenium wall at all. Imagine a house that does not get narrower as it meets the stage and that is fitted at the stage with a "proscenium opening protective" that provides the required fire rating between the house and stage with no wall. If one can build a theater without a proscenium wall why would anyone want to introduce an obstruction (the wall) that just limits the freedom of the directors and designers? Theaters have been built with no proscenium wall, but that's not appropriate for all theaters. Many theaters don't need the possibility of an unlimited connection between the house and stage, and many artistic directors still want to work inside a proscenium opening.

What emerges is that the stage and proscenium sizes are artistic and stylistic decisions more than they are technical decisions, and should be derived carefully after considering the ambitions of the directors and designers as much as the budget and the site. Stagehouse and proscenium sizes should not be copied out of a textbook nor be driven by technical rule-of-thumb.

Obstructions

Obstructions ruin a stage. We advise the design team at every phase of the project that no other space or building trade should intrude upon the stage space. In the architect's terminology, the stage is not a "chase". Just the trades that serve the stage, such as stage roof drains, stage sprinklers, stage ducts, stage conduit, stage heating pipes, stage wind braces, and so on are difficult enough to accommodate and coordinate with stage functions without also accommodating work that serves other spaces. To a mechanical engineer the stage and orchestra pit look like wonderful empty spaces through which to run pipes and ducts into the rest of the building. This must not be allowed. To the architect the stage looks like wonderful empty space through which to run egress stairs and vestibules. This must not be allowed. Good stages have no obstructions.

Home · Articles